By Jan Baetens

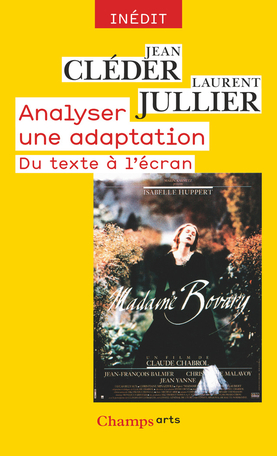

Jean Cléder & Laurent Jullier

Analyser une adaptation. Du texte à l’écran

Paris : Flammarion, 2017 (« Champs Arts »), 410 p.

ISBN : 9782081395954 (15 euros)

For many years, adaptation studies have been the core business of film and literature studies. The often sterile debates address issues of fidelity as well as the progressive opening of adaptation studies to other media than just film and literature. Co-authored by two leading French film scholars with an impressive pedigree, Jean Cléder and Laurent Jullier, this important book helps reframe both issues, while breaking new ground in this vital field of research.

On the one hand, Cléder and Jullier propose to study adaptations as interpretations, that is, as new works that offer a certain point of view and a new perspective on the adapted work. A clever and nuanced answer to the many problems raised by fidelity discussions, since it avoids direct comparison of source and target, while at the same time keeping a creative relationship between both. On the other hand, Analyser une adaptation demonstrates the usefulness of sticking to close-reading and meticulous exploration of the verbal and the audiovisual, whose medium-specific features should not be discarded in favor of a more generalizing, for instance historical or cultural examination (which does not mean that the historical and cultural context of the analysis is neglected in this book).

The importance of this publication exceeds, however, these global and more institutional considerations, for Analyser une adaptation, which I hope will soon be translated in English, is really the book for which all film scholars, theoreticians as well as teachers, have been anxiously waiting (in that regard, I would like to compare the possible impact of this book to that of Jacques Aumont’s 1990 The Image, a game-changer in the field of visual studies). I would like to foreground here four qualities, each of them already remarkable in itself. First of all, this book demonstrates the possibility of making a technical, even microscopic analysis of adaptation, and it does so with the help of many, excellently chosen examples. The analysis of the “distance” between character and camera, an often -overlooked feature, is a significant renewal of the well-known but not always correctly understood close-up/medium shot/long shot approach. Second, the book succeeds in encouraging its readers to start loving this kind of technical analysis, sometimes considered boring or shallowly mechanic. Cléder and Jullier show very convincingly that extreme close-reading matters and that it discloses key aspects of film adaptations. Third, this book also offers a two-way approach of film and literature, paying as much attention to the verbal adaption of images as to the audiovisual adaptation of texts, thus creating (finally!) a more encompassing reading of word and image in the field of film studies. Fourth (but certainly not last), Analyser une adaptation is a work that proves helpful to both scholars and students. The former will find in it an invitation to rethink many of their concepts and perhaps attitudes. The latter are offered a hands-on approach of adaptation that will prove supportive in more than just the classes on cinema.

Simon Leys (pseudonym of Pierre Ryckmans, 1935-2014) is a great example of this humanist ideal. As a law and art history student in Leuven and the representative of a students’ magazine, he was offered the possibility to go to China for one month, an experience that dramatically changed his life. He started to learn Chinese and, after his graduation, left for Taiwan where he defended a PhD on Chinese painting before moving to Hong Kong and eventually Canberra and Sydney, Australia, where he became a professor of Chinese culture. Ryckmans had to take a pseudonym when publishing the book that made him world-famous, The Chairman’s New Clothes: Mao and the Cultural Revolution (1971), the first critical account of the Chinese Cultural Revolution.

Simon Leys (pseudonym of Pierre Ryckmans, 1935-2014) is a great example of this humanist ideal. As a law and art history student in Leuven and the representative of a students’ magazine, he was offered the possibility to go to China for one month, an experience that dramatically changed his life. He started to learn Chinese and, after his graduation, left for Taiwan where he defended a PhD on Chinese painting before moving to Hong Kong and eventually Canberra and Sydney, Australia, where he became a professor of Chinese culture. Ryckmans had to take a pseudonym when publishing the book that made him world-famous, The Chairman’s New Clothes: Mao and the Cultural Revolution (1971), the first critical account of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The Lonely Hearts Hotel is the most recent novel by Canadian author, Heather O’Neil. It is the story of Pierrot and Rose; orphans, who both, in differing circumstances, nearly die at birth but miraculously survive against the odds. O’Neil’s novel begins against the backdrop of Pierrot’s and Rose’s childhoods, spent together at a Montreal orphanage in the early part of the twentieth-century. Both the nuns and the other children at the orphanage recognize that Pierrot and Rose are special; through music, dance, and play they manage to cultivate pockets of joy out of their dismal realities. While the nuns do their best to stifle Pierrot’s and Rose’s flourishing (as well as their connection), the other children delight in the magic that is brought into their otherwise fragile and violent existences. From here, the novel follows the two protagonists as life takes them in differing yet equally dark directions. Despite their separation, both hold onto their childhood promise to one another of a shared future. Nineteen-thirties Montreal becomes the stage for make-believe, unlikely friendships, poverty, theft, theater-troops, addiction, sex, and mafia-life. Written with unparalleled imagery in the form of metaphor and simile, O’Neil’s prose come alive in the imagination like an illustrated fable stretching out before the reader, spontaneously coming into being as each page is turned. When a nun is described as reminding Pierrot of “a glass of milk” and “clean sheets blowing in the wind at the exact moment when the water evaporated from them and they became dry and light and easy again,” the reader is not tripped up by this strange mix of subject/object but instead sees the sunlight on those sheets, the rolling hills in the distance, and almost smells the fresh country air.

The Lonely Hearts Hotel is the most recent novel by Canadian author, Heather O’Neil. It is the story of Pierrot and Rose; orphans, who both, in differing circumstances, nearly die at birth but miraculously survive against the odds. O’Neil’s novel begins against the backdrop of Pierrot’s and Rose’s childhoods, spent together at a Montreal orphanage in the early part of the twentieth-century. Both the nuns and the other children at the orphanage recognize that Pierrot and Rose are special; through music, dance, and play they manage to cultivate pockets of joy out of their dismal realities. While the nuns do their best to stifle Pierrot’s and Rose’s flourishing (as well as their connection), the other children delight in the magic that is brought into their otherwise fragile and violent existences. From here, the novel follows the two protagonists as life takes them in differing yet equally dark directions. Despite their separation, both hold onto their childhood promise to one another of a shared future. Nineteen-thirties Montreal becomes the stage for make-believe, unlikely friendships, poverty, theft, theater-troops, addiction, sex, and mafia-life. Written with unparalleled imagery in the form of metaphor and simile, O’Neil’s prose come alive in the imagination like an illustrated fable stretching out before the reader, spontaneously coming into being as each page is turned. When a nun is described as reminding Pierrot of “a glass of milk” and “clean sheets blowing in the wind at the exact moment when the water evaporated from them and they became dry and light and easy again,” the reader is not tripped up by this strange mix of subject/object but instead sees the sunlight on those sheets, the rolling hills in the distance, and almost smells the fresh country air. Like a Chef is a work with a double focus. It is, in the very first place, an autobiography, or at least in part, but it is also a vibrant presentation of gastronomy, more particularly the various types of the “new cuisine”, an approach to cooking and food presentation in French cuisine. In contrast to classic cuisine, an older form of haute cuisine, new cuisine is characterized by lighter, more delicate dishes, an increased emphasis on presentation, and the desire to make cooking as innovative and surprising as, for instance, art. Both perspectives come neatly together in the person of Benoît Peeters who, as a young author (he published his first novel at age 20), had to try to make a living. His love for food as well as his lust for innovation encouraged him to try his luck as a cook, and the book reports his many gastronomic adventures in the first years of his adult life, from the discovery –a nearly religious epiphany– of the new cuisine in the restaurant of the Troisgros brothers to his personal contacts with some great chefs such as Willy Slawinksi from the Apicius restaurant in Ghent and Ferrian Adrià from El Bulli.

Like a Chef is a work with a double focus. It is, in the very first place, an autobiography, or at least in part, but it is also a vibrant presentation of gastronomy, more particularly the various types of the “new cuisine”, an approach to cooking and food presentation in French cuisine. In contrast to classic cuisine, an older form of haute cuisine, new cuisine is characterized by lighter, more delicate dishes, an increased emphasis on presentation, and the desire to make cooking as innovative and surprising as, for instance, art. Both perspectives come neatly together in the person of Benoît Peeters who, as a young author (he published his first novel at age 20), had to try to make a living. His love for food as well as his lust for innovation encouraged him to try his luck as a cook, and the book reports his many gastronomic adventures in the first years of his adult life, from the discovery –a nearly religious epiphany– of the new cuisine in the restaurant of the Troisgros brothers to his personal contacts with some great chefs such as Willy Slawinksi from the Apicius restaurant in Ghent and Ferrian Adrià from El Bulli. The book has indeed an exceptionally long blurb section, which starts at the front cover, continues on the back cover, appears to cheer up the interior cover pages and quite a lot of the front matter. In short: no less than nine pages of praise of a “superb”, breathtaking”, and “brilliant” book, which only made me yawn.

The book has indeed an exceptionally long blurb section, which starts at the front cover, continues on the back cover, appears to cheer up the interior cover pages and quite a lot of the front matter. In short: no less than nine pages of praise of a “superb”, breathtaking”, and “brilliant” book, which only made me yawn. James I. Porter’s “Disfigurations: Erich Auerbach’s Theory of Figura” (Critical Inquiry, vol. 44-1, 2017, pp., 80-113) is one of the best essays I’ve read in recent months. It is a rereading of Erich Auerbach’s seminal study “Figura” of 1938 as well as a vital contribution to the cultural analysis of reading and storytelling, not in the empirical, but in the philosophical sense of the word.

James I. Porter’s “Disfigurations: Erich Auerbach’s Theory of Figura” (Critical Inquiry, vol. 44-1, 2017, pp., 80-113) is one of the best essays I’ve read in recent months. It is a rereading of Erich Auerbach’s seminal study “Figura” of 1938 as well as a vital contribution to the cultural analysis of reading and storytelling, not in the empirical, but in the philosophical sense of the word. For contemporary readers, however, Auerbach (1892-1957) is not the author of “Figura” but of Mimesis, written in exile between 1942 and 1945. Mimesis, which has never been out of print, is a study of the progressive emergence of “realism” in Western literature, that is of a way of interpreting that emphasizes the literal, not the symbolic meaning of the text, even if the literal meaning is open to debate, and that highlights how stories are rooted in concrete historical and material contexts. Auerbach scholarship generally focuses either on “Figura” or on Mimesis, but rarely brings together both studies, as if the author’s attention had simply shifted from classic philology and symbolic reading to comparative literature and realism. Yet in “Disfigurations”, this is exactly what James I. Porter does: rereading Mimesis in light of “Figura”, not in order to find a dialectic synthesis of the two apparently conflicting poles, but in order to disclose the profound continuity in Auerbach’s thinking as well as the crucial importance of “realism” in the genesis and meaning of Mimesis itself, which was written in exile in Turkey (a then militantly nonreligious state). Auerbach’s great book, Porter argues, should be read not just as a defense of Western realism, but as a reaction against the symbolic –be it figural or, worse, allegorical– that was defended by Nazi philosophy, philology, theology, etc., to delete not only Jewish history and Jewish tradition but the typical way in which the Jewish tradition read its own stories, namely as realist stories deeply rooted in precise historical conditions yet utterly ambivalent and ambiguous –and therefore inevitably open to endless interpretation and reinterpretation and permanently inviting us to question our own relationship to the specific environment in which we are living here and now (including our fundamental incapacity to produce final and fixed meanings).

For contemporary readers, however, Auerbach (1892-1957) is not the author of “Figura” but of Mimesis, written in exile between 1942 and 1945. Mimesis, which has never been out of print, is a study of the progressive emergence of “realism” in Western literature, that is of a way of interpreting that emphasizes the literal, not the symbolic meaning of the text, even if the literal meaning is open to debate, and that highlights how stories are rooted in concrete historical and material contexts. Auerbach scholarship generally focuses either on “Figura” or on Mimesis, but rarely brings together both studies, as if the author’s attention had simply shifted from classic philology and symbolic reading to comparative literature and realism. Yet in “Disfigurations”, this is exactly what James I. Porter does: rereading Mimesis in light of “Figura”, not in order to find a dialectic synthesis of the two apparently conflicting poles, but in order to disclose the profound continuity in Auerbach’s thinking as well as the crucial importance of “realism” in the genesis and meaning of Mimesis itself, which was written in exile in Turkey (a then militantly nonreligious state). Auerbach’s great book, Porter argues, should be read not just as a defense of Western realism, but as a reaction against the symbolic –be it figural or, worse, allegorical– that was defended by Nazi philosophy, philology, theology, etc., to delete not only Jewish history and Jewish tradition but the typical way in which the Jewish tradition read its own stories, namely as realist stories deeply rooted in precise historical conditions yet utterly ambivalent and ambiguous –and therefore inevitably open to endless interpretation and reinterpretation and permanently inviting us to question our own relationship to the specific environment in which we are living here and now (including our fundamental incapacity to produce final and fixed meanings). Hazan’s crossing of Paris leads him from the south (Ivry) to the north (Saint-Denis) and focuses on the “center” of Paris; that is, the twenty neighborhoods that can be found “inside” the beltway, which both prevents the traditional city to grow and protects it from the dangers of the less wealthy suburban circles that surround it (some French view Saint-Denis the way some Belgians view Molenbeek). Yet the margins are permanently present: geographically, humanly, culturally, politically speaking. The major aim of Hazan’s book is to disclose the “popular” aspects of the capital, which resist the galloping gentrification, and to highlight the continuity of a revolutionary tradition in the city.

Hazan’s crossing of Paris leads him from the south (Ivry) to the north (Saint-Denis) and focuses on the “center” of Paris; that is, the twenty neighborhoods that can be found “inside” the beltway, which both prevents the traditional city to grow and protects it from the dangers of the less wealthy suburban circles that surround it (some French view Saint-Denis the way some Belgians view Molenbeek). Yet the margins are permanently present: geographically, humanly, culturally, politically speaking. The major aim of Hazan’s book is to disclose the “popular” aspects of the capital, which resist the galloping gentrification, and to highlight the continuity of a revolutionary tradition in the city.