Recently Charlie Johns edited an extremely interesting book that works through the argument that neurosis is the dominant condition of our society today. An array of thinkers, as Graham Harman, Benjamin Noys, Patricia Reed, Dany Nobus, John Russon, Charles Johns and Katerina Kolozova, have addressed the following question: How can the concept of ‘Neurosis’ help us understand the new digitized world in which we live and our place in it?

An interview with Charlie Johns and Anna Zhurba of the Moscow Museum of Modern Art (MMOMA).

A.Z.: What is the relationship between technological progress and neurosis?

C.J.: The phrase ‘technological progress’ is already a dubious one; is progress determined culturally qua differences, and what are the criteria for progress to be achieved (standard of living etc.)? If we made an analogy between progress and proliferation we could, however, suggest that neurosis is progress. Why? Neurosis is essentially the hyper-sensitivity towards - and determination of - concepts. Whether we describe concepts as a type of clothing draped over the ‘unknown’ world, or whether we describe concepts as autopoietic agencies in their own right, it still amounts to the same thing on a phenomenological level; we interact, assign and orient our lives via concepts (or - if you will - conceptual sign systems/semiotics). Second nature is superimposed onto a putative first nature and it is inevitable that further concepts will be produced and ensue. In this sense we are living in a highly proliferated conceptual world, where many concepts do not even refer to an object, representation, or what some philosophers have called ‘the real’. Neurosis is the exaggeration of such a viewpoint (which can be found in various thinkers such as Hegel, Deleuze and especially Baudrillard).

It would actually be more cogent to think of concepts as a type of technology, after all, every form of naming and crafting is also a conceptual form (it is a conceptual signature onto putative external/material reality). The world of objects and their uses is also a world of conceptual functions (remember that we put those uses there in the first place), a conceptual cartography which helps us navigate as humans. Following Heidegger, and later Wittgenstein, we become aware that we are always already within this conceptual technology; taking up speech and language for instance, using pre-existing equipment to enable mastery over ourselves and our world. What comes to the fore in my concept of neurosis is that such ‘embeddedness’ in the world could also be limiting and ignorant; Wittgenstein famously stated that “when I obey a rule, I do not choose, I obey the rule blindly” (Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations). Neurosis is the pessimistic counterpart to the Hegelian notion that a culture can be swept along by a certain conceptual paradigm, or the Humean notion that we gain knowledge through experience qualified through custom and habit (i.e compulsive repetition).

Regardless of the philosophical assertion that concept and craft cannot be reduced to either one domain, we can say in an everyday sense that technology (as we know it) aids this neurosis because it constantly generates and re-inserts concepts/symbols back into the lived social experiential domain, creating a high intensity of concepts and a type of redoubling of the concept onto the human (think advertisements) that are akin to traumatising the subject (technologies modes of distraction, seduction and capture).

Neurosis is a philosophy ‘beyond good and evil’ in the sense that it is interested in the intensity, exaggeration, proliferation and dissemination of concepts without recourse to judging them as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ (this is not to say that semantics is absent in the concept).

Neurosis does not necessarily mean ‘bad’, it is used partly to bring to light how we are affected by concepts, as Marcuse and Fromm knew, ‘bad’ and ‘good’ are only relative to the ideologies of a society. Using the Freudian dynamic of the pleasure principle may be an interesting exercise however. Neurosis is against any humanist notion of a ‘way out’ of the impasse of determinism, it in-fact believes that constructs such as ‘genius’ and ‘freedom’ should be reconceptualised as compulsive repetitious acts of concept production as opposed to any moral, supernatural or metaphysical definition.

I am giving you a philosophical answer to your question, however, one can easily see a relatively straightforward link between technological ‘progress’ and neurosis, such a link being historical. That link would be the instantiation of the concept of neurosis by William Cullen in the mid-eighteenth century and the Industrial Revolution arising at the same time. Both events are in many ways interchangeable; the neurotic desire for totalization and positivism found in the spirit of the Industrial Revolution, and the sudden affair of the human sensorium with the exotic and intense rates of speed, power, seduction, and claustrophobia of technology that made us in turn slow, weak, naive and powerless, such effects condensing as forms of neuroses (foreign thoughts and general anxiety).

In many ways the Industrial Revolution has simply proliferated in our present epoch (one can call it Advanced Capitalism or Late Capitalism or Globalization etc). When Psychoanalysis came onto the scene with Freud and Jung, a similar event had happened, a kind of impasse where the individual was reasserted within the domain of technological determinism. It was in a sense necessary that repressed powers of sexuality, violence and taboo were to be disclosed by psychoanalysis, as such powers were in contradistinction to technology (i.e technology was not thought of as sexual or rebellious, these were traits affirmed by man in human nature). The relation of psychology and technology that I am personally interested in is not a contra-distinctive one however (a relation made by differences) but rather one of interconnectedness; the technological presentation of the subconscious into the realm of photography, film and animation, and vice versa, the arrival of such visual technology into the human mind, man’s thoughts and his dreams. For me Walter Benjamin becomes a great guide for this phenomenon. Using his theory of the Optical Unconscious we simultaneously become aware of the ‘repressed’ phenomena in visual culture ( disclosing the twenty four frames that make up a filmic second, the zoom of the camera lense penetrating into a new world of images etc) and also the power of the image itself. All one needs is a representation and that is enough to get the neurosis started. The representation in-fact takes on a new meaning distinct from the object or referent and harnesses its own phenomenological powers (look at the subliminal power of the image, it’s ability to become recognized in collective consciousness such as certain brands and icons). This is partly why Jean Baudrillard characterised the image as “fundamentally immoral” (Baudrillard Live, Selected Interviews, Gane, Routledge, 1993). As I have stated in my introduction to The Neurotic Turn (Repeater Books, 2017), this relation between contemporary human consciousness (neurosis) and technology can be sentimentalised in different ways. There is a kind of Frankenstein effect whereby the technology that was implemented and integrated by society for utilitarian purposes has reached the point where it has transgressed such moral and economic goals and is now the source of our ills (we watch technology turn its head away in neglect of us, like how Dr Frankenstein does with his monster). Or, we can be less romantic and argue that there should be no lament of The Real, or of the ‘peasant’ life, and instead insist that conceptual formation would have become highly simulated in its own right anyway, or that a legitimate contemporary ontology would have to do away with The Real (in any objective sense) and understand processes of neurosis, extrapolation and simulation as part of nature ‘in-itself’.

A.Z.: Do you see any productive/ positive outcome in liberating neurosis from its repressed status?

C.J.: Yes I do very much. Similar to the Enlightenment spirit, I believe we as humans can be a bit more sensitive, aware and cautious of the prejudice and bias we act out on a minute to minute basis. By learning to heuristically separate ourselves from the concepts we inhabit and produce, we can take an analytical approach which is both enlightened, post-human and traditionally psychological; 1) we can analyse the criteria or strength of the concepts at our disposal and can question which concepts may be beneficial and non-beneficial to our objectives and our behaviour. 2) we can move beyond the embodied, impassioned view of concept formation as inextricably linked to human subjectivity and our drives (seen in Hume and areas of Nietzsche). 3) we can ask why a person is articulating certain concepts in certain ways in order to define the problem in concept production, transmission and reception, as opposed to defining the problem in an individual(this notion is sympathetic to various ‘criminals’ outlawed and the sidelining of the mentally ill in society). The concepts at our disposal are precisely that; ours, and we must learn where they come from and under what circumstance they can prove to have purchase. Although this may sound inhuman and rationalistic, the alternative would be technological nihilism or solipsistic Nietzscheanism, you choose. In many ways I am still following that tradition of psychology and socio-cultural criticism found in Marcuse and Fromm; we need to liberate/ disclose what is left repressed by ourselves and our institutions, in order to guarantee a less one-dimensional man and culture. Saying this, however, I do not believe that neurosis truly can be liberated; psychoanalysis does not assume a perfect end state (in fact it denies the very possibility and is thoroughly pessimistic in this respect). Psychoanalysis, I believe, is more about process and transformation. All we can hope to do is transform ourselves in relation to the world we are implicated in. The worst situation would be a stalemate. That for me is the true meaning of nihilism.

A.Z.: How do public/collective and private/subjective realms relate to each other in your reading of the idea of the neurotic?

C.J.: There is no distinction in my view. As I have stated above, the intersubjectivity of man and technology has always been there, in concepts, in language, in craft, in techne, in society etc. The main difference now is how we view this intersubjectivity; at first we acknowledged the union but believed that it was primarily for man’s benefit. We used philosophical notions such as freedom, final cause, virtue and teleology to qualify the position that it was the realm of man who had goals and purpose, technology being simply a means to an end. With the advent of various doctrines such as Marxism this sentiment had changed and there is a much more negative (albeit only at first) view of technology as deterministic and all-pervasive. The reason I bring this up is because I think technology allows us to think about the private/public dichotomy with more clarity. Language is always already a technology where one is implicated within but never fully owns. Perception, likewise, is always produced socially, and such an ‘order of things’ is not found explicitly within one’s own perception. The argument for this interconnectedness has been described since the dawn of Western philosophy (but much development has been made in the Continental tradition of philosophy). I am probably the most pessimistic philosopher of this ‘deterministic’ interconnected tradition (following Baudrillard in many respects). Neurosis attempts to characterise the contamination (Derrida) and bricolage (Levi Strauss) of meaning within contemporary consciousness and hence the conflation of the two poles private and public. Someone is always plugged into someone else, speaking as, for or through someone else (this is the entire goal of capitalism; retail service, customer service, etc.). On the other side, the ‘private’ domain has never been exteriorised more than in the 21st century; with the advent of facebook, instagram, twitter etc personal life is public life and all positive meaning between the chafing of the two has disappeared. What I am more interested in nowadays is not the private/public dichotomy but the secret/non-secret dichotomy. The true secret, always there in psychoanalysis, always there in the mad and the criminally insane, the concept that one man may be hiding, is keeping, like a form of property etc. I do not wish to know these secrets, and perhaps this is the last fruitful life of the romantic concept of authenticity or identity within human civilization.

A.Z.: What are the main historical shifts in the popular perception of the neurotic?

C.J.: I would not claim to be an expert at answering this question, but I believe the shift is enormous in many ways. If we even attempt to anchor it to its psychological home we will find it challenging. Neurosis is disclosed in 1769 by Dr. William Cullen. Not to take it away from Dr. Cullen but we can gauge philosophically why this had to be the case; psychology had ‘developed’ to a point in the eighteenth century where ‘symptoms’ were assumed to come from exclusively material, biological and organic processes. Many mental disturbances (such as neurosis and psychosis) could not be discerned by this method (physiologically or causally). At the time, scientific legitimacy depended on its allegiance to the material world hypothesis (against superstition etc). However, in the mid 1700’s the enlightenment ideal of the individual was taking place (one can see Immanuel Kant’s debt to the father of Early Modern Philosophy Rene Descartes) and this was against the scientific realism supporting certain psychological discourses at the time. Hence ‘neurosis’ was adopted by this new mind-set and disclosed as both mental and subjective (it was later adopted in the same non-scientific way by Romanticism and given a kind of ‘tension’/ cathexis (the moving elements, the relation between man and nature) as well as a solitary denotation). Before then, in the writings of Christian Wolffe, and even in the pre-Socratics, neurosis was characterised as either ‘mind’ or ‘soul’ (soul pertaining to the whole world, the ‘world-soul’). Although I find these earlier characterisations illuminating, I find that Cullen picked up upon the discomforting quality of the psyche, and this is of main interest to me. So already there you have a large shift of the term psyche; from soul, spirit, nature, to simply ‘the mental’, and later, with Cullen, the term neurosis is a kind of instantiation; the moment when mind and spirit is reflected in an eighteenth century mind now bridled with ideas and passing into a new phase of alienation. In many ways I see Cullen’s instantiation of neurosis as the condensation of the Gothic quality of mind; the ghosts in the machine, the nightmare images of irrationality (think of Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters).

In popular culture, however, neurosis seems to have been embraced (Patricia Friedrich talks about those characters we love, such as those played by Woody Allen and the character of Patrick Bateman in American Psycho etc., in the book The Neurotic Turn, Repeater Books). In literature too we have a line of thinkers from Dostoevsky, Bataille and Barthes, and later we could say that almost everyone in the 21st century has an element of what Freud had called ‘narcissistic personality disorder. ’ As I said, I am not an expert in the social representation of the neurotic, but it is obvious - at least on a surface level - that the neurotic has been one of the most accepted ‘outsider’ figures in the twentieth and twenty-first century. Research has to be done into exactly why this is. I believe that it is because the traditional psychological neurotic was diagnosed with what we are all beginning to realise we have too, and was always there in some repressed form; a renewed sensitivity to the onslaught of concepts, an awareness of the compulsive repetition inherent in any act of making meaningful, the daunting anxiety of feeling the value of personal identity wither away in the face of neutral, indifferent postmodernism.

A.Z.: What is your description of neurosis and is it a ‘first world problem’?

C.J.: A neurosis is any trajectory of thought that you abide by (whether willingly or unwillingly). It names the process of experiencing consciousness without knowing where it comes from and where it is leading you. You are in a sense ‘in the middle’ of consciousness, hence, you are the patient, or the victim. In this sense neurosis could not be considered as only a first world problem. Every human participates in this role of consciousness, just as everyone participates in Geist in Hegel. However, yes, neurosis has always been an exaggerated form of thought-processing, the traditional neurotic (of the diagnosed kind) gives us a clue as to the future state of cognition, he/she is simply the first that recognises it. Most of our thoughts do not have direct reference to ‘physical reality’. I begin to think about something that I am perhaps meant to do, told by someone else. I begin to think about how someone else might think about me. I begin to realise that the objective of my thoughts are simply to attain symbolic/imaginary goals such as sexual, monetary and social status. I begin to understand that the desire intrinsic to my thought processes have nothing to do with maintaining social stability, they do not uphold any moral sense or moral value etc. The proliferation and sensitivity of thought in neurosis is relative to the dissolution and homogenising of traditional meaning (the subsequent relentless production of commodity fetishism everywhere in life). In this respect you could say that ‘neurosis’ is an anthropological description of thought in the ‘first-world’ … but neurosis does not go away if you find concrete uses for it in nature; the eskimo is just as neurotic when he attributes eleven different meanings to the phenomenon snow.

The Neurotic Turn book is now available through Repeater Books.

https://repeaterbooks.com/product/the-neurotic-turn-inter-disciplinary-correspondences-on-neurosis/

Like a Chef is a work with a double focus. It is, in the very first place, an autobiography, or at least in part, but it is also a vibrant presentation of gastronomy, more particularly the various types of the “new cuisine”, an approach to cooking and food presentation in French cuisine. In contrast to classic cuisine, an older form of haute cuisine, new cuisine is characterized by lighter, more delicate dishes, an increased emphasis on presentation, and the desire to make cooking as innovative and surprising as, for instance, art. Both perspectives come neatly together in the person of Benoît Peeters who, as a young author (he published his first novel at age 20), had to try to make a living. His love for food as well as his lust for innovation encouraged him to try his luck as a cook, and the book reports his many gastronomic adventures in the first years of his adult life, from the discovery –a nearly religious epiphany– of the new cuisine in the restaurant of the Troisgros brothers to his personal contacts with some great chefs such as Willy Slawinksi from the Apicius restaurant in Ghent and Ferrian Adrià from El Bulli.

Like a Chef is a work with a double focus. It is, in the very first place, an autobiography, or at least in part, but it is also a vibrant presentation of gastronomy, more particularly the various types of the “new cuisine”, an approach to cooking and food presentation in French cuisine. In contrast to classic cuisine, an older form of haute cuisine, new cuisine is characterized by lighter, more delicate dishes, an increased emphasis on presentation, and the desire to make cooking as innovative and surprising as, for instance, art. Both perspectives come neatly together in the person of Benoît Peeters who, as a young author (he published his first novel at age 20), had to try to make a living. His love for food as well as his lust for innovation encouraged him to try his luck as a cook, and the book reports his many gastronomic adventures in the first years of his adult life, from the discovery –a nearly religious epiphany– of the new cuisine in the restaurant of the Troisgros brothers to his personal contacts with some great chefs such as Willy Slawinksi from the Apicius restaurant in Ghent and Ferrian Adrià from El Bulli. In the book 50 Key Terms in Contemporary Cultural Theory, edited by Joost de Bloois, Stijn De Cauwer and Anneleen Masschelein, 50 important terms are explained by 35 scholars. In short texts, the history and context of each term is explained, as well as the debates that the term has triggered. Each text is followed by a short bibliography for further reading. There are terms that help us to understand contemporary political challenges: precarity, immaterial labor, biopolitics, common(s), anthropocene, surveillance, debt, cultural memory, agonism, multitude, spectacle, post-truth and political theology. Some terms help us to understand new media developments: algorithm, open access, digital cultural heritage, convergence, archive and network. Other terms help us to come to terms with the diversity of human life: intersectionality, heteronormativity, posthumanism, postfeminism, postcolonialism and crip theory. Some terms are deceptively simple but they have a complex history and their use has become the object of critical research in the Humanities: love, war, life, justice, immunity, noise, image, participation, crisis, creativity, performance, rhythm, curating and that mysterious notion people like to use so easily, culture. Certain terms may be considered to be somewhat outdated in the public opinion but they have continued to be relevant in the Humanities: utopia, class and ideology. Finally, there are terms which have become much-debated theoretical terms: accelerationism, plasticity, affect, individuation, speculation, medicalization and the sensible.

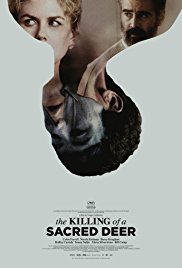

In the book 50 Key Terms in Contemporary Cultural Theory, edited by Joost de Bloois, Stijn De Cauwer and Anneleen Masschelein, 50 important terms are explained by 35 scholars. In short texts, the history and context of each term is explained, as well as the debates that the term has triggered. Each text is followed by a short bibliography for further reading. There are terms that help us to understand contemporary political challenges: precarity, immaterial labor, biopolitics, common(s), anthropocene, surveillance, debt, cultural memory, agonism, multitude, spectacle, post-truth and political theology. Some terms help us to understand new media developments: algorithm, open access, digital cultural heritage, convergence, archive and network. Other terms help us to come to terms with the diversity of human life: intersectionality, heteronormativity, posthumanism, postfeminism, postcolonialism and crip theory. Some terms are deceptively simple but they have a complex history and their use has become the object of critical research in the Humanities: love, war, life, justice, immunity, noise, image, participation, crisis, creativity, performance, rhythm, curating and that mysterious notion people like to use so easily, culture. Certain terms may be considered to be somewhat outdated in the public opinion but they have continued to be relevant in the Humanities: utopia, class and ideology. Finally, there are terms which have become much-debated theoretical terms: accelerationism, plasticity, affect, individuation, speculation, medicalization and the sensible. The film opens with an uncomfortable scene, thrusting the viewer head on to the heart of the matter. This initial anxiety rings like white noise throughout the film, increasing and decreasing in pitch, but penetratingly constant. Its only pitch-equal is the closing scene that, while quite a different image, echoes the initial degree of discomfort with which the viewer has been coping for the last 115 minutes.

The film opens with an uncomfortable scene, thrusting the viewer head on to the heart of the matter. This initial anxiety rings like white noise throughout the film, increasing and decreasing in pitch, but penetratingly constant. Its only pitch-equal is the closing scene that, while quite a different image, echoes the initial degree of discomfort with which the viewer has been coping for the last 115 minutes. James I. Porter’s “Disfigurations: Erich Auerbach’s Theory of Figura” (Critical Inquiry, vol. 44-1, 2017, pp., 80-113) is one of the best essays I’ve read in recent months. It is a rereading of Erich Auerbach’s seminal study “Figura” of 1938 as well as a vital contribution to the cultural analysis of reading and storytelling, not in the empirical, but in the philosophical sense of the word.

James I. Porter’s “Disfigurations: Erich Auerbach’s Theory of Figura” (Critical Inquiry, vol. 44-1, 2017, pp., 80-113) is one of the best essays I’ve read in recent months. It is a rereading of Erich Auerbach’s seminal study “Figura” of 1938 as well as a vital contribution to the cultural analysis of reading and storytelling, not in the empirical, but in the philosophical sense of the word. For contemporary readers, however, Auerbach (1892-1957) is not the author of “Figura” but of Mimesis, written in exile between 1942 and 1945. Mimesis, which has never been out of print, is a study of the progressive emergence of “realism” in Western literature, that is of a way of interpreting that emphasizes the literal, not the symbolic meaning of the text, even if the literal meaning is open to debate, and that highlights how stories are rooted in concrete historical and material contexts. Auerbach scholarship generally focuses either on “Figura” or on Mimesis, but rarely brings together both studies, as if the author’s attention had simply shifted from classic philology and symbolic reading to comparative literature and realism. Yet in “Disfigurations”, this is exactly what James I. Porter does: rereading Mimesis in light of “Figura”, not in order to find a dialectic synthesis of the two apparently conflicting poles, but in order to disclose the profound continuity in Auerbach’s thinking as well as the crucial importance of “realism” in the genesis and meaning of Mimesis itself, which was written in exile in Turkey (a then militantly nonreligious state). Auerbach’s great book, Porter argues, should be read not just as a defense of Western realism, but as a reaction against the symbolic –be it figural or, worse, allegorical– that was defended by Nazi philosophy, philology, theology, etc., to delete not only Jewish history and Jewish tradition but the typical way in which the Jewish tradition read its own stories, namely as realist stories deeply rooted in precise historical conditions yet utterly ambivalent and ambiguous –and therefore inevitably open to endless interpretation and reinterpretation and permanently inviting us to question our own relationship to the specific environment in which we are living here and now (including our fundamental incapacity to produce final and fixed meanings).

For contemporary readers, however, Auerbach (1892-1957) is not the author of “Figura” but of Mimesis, written in exile between 1942 and 1945. Mimesis, which has never been out of print, is a study of the progressive emergence of “realism” in Western literature, that is of a way of interpreting that emphasizes the literal, not the symbolic meaning of the text, even if the literal meaning is open to debate, and that highlights how stories are rooted in concrete historical and material contexts. Auerbach scholarship generally focuses either on “Figura” or on Mimesis, but rarely brings together both studies, as if the author’s attention had simply shifted from classic philology and symbolic reading to comparative literature and realism. Yet in “Disfigurations”, this is exactly what James I. Porter does: rereading Mimesis in light of “Figura”, not in order to find a dialectic synthesis of the two apparently conflicting poles, but in order to disclose the profound continuity in Auerbach’s thinking as well as the crucial importance of “realism” in the genesis and meaning of Mimesis itself, which was written in exile in Turkey (a then militantly nonreligious state). Auerbach’s great book, Porter argues, should be read not just as a defense of Western realism, but as a reaction against the symbolic –be it figural or, worse, allegorical– that was defended by Nazi philosophy, philology, theology, etc., to delete not only Jewish history and Jewish tradition but the typical way in which the Jewish tradition read its own stories, namely as realist stories deeply rooted in precise historical conditions yet utterly ambivalent and ambiguous –and therefore inevitably open to endless interpretation and reinterpretation and permanently inviting us to question our own relationship to the specific environment in which we are living here and now (including our fundamental incapacity to produce final and fixed meanings).

Jean-Christophe Menu is one of the major voices of alternative comics in France, both as an author and as the co-founder of L’Association, the leading publisher of French comix in the period of his 20 years editorship (he resigned a couple of years ago). He is above all a living paradox: the angry young man of the French bande dessinée scene, he is also the holder of a PhD on the subject (moreover an excellent one, frequently used and quoted in academic research: La Bande dessinée et son double, 2011); the living example of authentic visual thinking, he is also an author who does not make any real distinction between his drawings and his writings. His new book is the perfect yet open synthesis of all these forces and tendencies.

Jean-Christophe Menu is one of the major voices of alternative comics in France, both as an author and as the co-founder of L’Association, the leading publisher of French comix in the period of his 20 years editorship (he resigned a couple of years ago). He is above all a living paradox: the angry young man of the French bande dessinée scene, he is also the holder of a PhD on the subject (moreover an excellent one, frequently used and quoted in academic research: La Bande dessinée et son double, 2011); the living example of authentic visual thinking, he is also an author who does not make any real distinction between his drawings and his writings. His new book is the perfect yet open synthesis of all these forces and tendencies.