Bozar – 09.12.2015 | 14:00 – 19:00 http://www.bozar.be/en/activities/121469-study-day-screenwriting-research-and-stereotypes

(Anglais – Engels – English)

FR En tant que média de masse, la télévision a un rayonnement très large. Bon nombre de séries télévisées de qualité et à succès font référence à l’histoire ou à des débats contemporains, et se basent sur des recherches approfondies pour créer des histoires convaincantes et des univers narratifs captivants et réalistes. À l’occasion de cette journée, nous souhaitons examiner le genre de recherches entreprises par les scénaristes pour créer des univers crédibles pour les séries. Nous désirons également questionner la recherche académique sur la télévision contemporaine. Dans quelle mesure la télévision renforce-t-elle ou conteste-t-elle les stéréotypes dominants (groupe ethnique, genre, sexualité) ? Les séries aspirent-elles à répondre aux problèmes sociopolitiques contemporains et à les influencer ? La culture télévisée contemporaine est-elle diversifiée, tant sur le plan de la production que de la représentation ? Quelles stratégies s’avèrent efficaces pour stimuler la diversité de manière crédible, tout en attirant de vastes publics ? Comment des récits locaux peuvent-ils toucher un public mondial ?

NL Als massamedium heeft de televisie een groot bereik en een grote aantrekkingskracht. Veel succesvolle televisieseries behandelen de geschiedenis en hedendaagse debatten, en steunen op heel wat researchwerk om goede verhalen met pakkende, realistische achtergronden te brengen. In dit gesprek belichten we welk soort research van scenaristen leidt tot boeiende werelden voor series en plaatsen we die research tegenover academisch onderzoek naar hedendaagse televisie. In welke mate bevestigt of weerlegt de televisie de gangbare stereotypes (ras, gender, seksualiteit)? Koesteren series de ambitie om hedendaagse politieke en sociale problemen aan te snijden en te beïnvloeden? Hoe divers is de hedendaagse televisiecultuur, zowel wat betreft de productie als de representatie? Wat zijn efficiënte strategieën om op een geloofwaardige manier diversiteit te stimuleren en toch een breed publiek aan te spreken? Hoe kunnen lokale verhalen en achtergronden een veel breder publiek aanspreken?

EN As a mass medium, television has a great reach and appeal. Many successful quality television series refer to history and contemporary debates, and use a lot of research work to create good stories and compelling, realistic story worlds. In this panel, we want to examine the kind of research that is done by screenwriter sin order to create strong series universes and enter into dialogue with academic research on contemporary television. To what extent does television both confirm and challenge prevailing stereotypes (race, gender, sexuality)? Do series aspire to address and also influence contemporary political and social problems? How diverse is contemporary television culture today, both on the level of production and on the level of representation? What are effective strategies to stimulate diversity in a credible way and still appeal to broad audiences? How can local stories and histories affect global audiences?

14:00 > 15:00 Frederik Dhaenens (BE) How (not) to represent sexual diversity: From queer over normal to normative

FR Depuis le 21ème siècle, les personnages lesbiens, gays, bisexuels ou transgenres (LGBT) ne sont plus absents ou représentés comme des stéréotypes monodimensionnels dans les séries télévisées. Pourtant, les représentations actuelles sont toujours élaborées pour correspondre au discours occidental normatif dominant sur le genre et la sexualité. Dans cette conférence, je montrerai les différentes manières de représenter des personnages LGBT et expliquerai pourquoi certaines d’entre elles peuvent être considérées comme stéréotypées ou offensantes alors que d’autres sont transgressives et dans l’esprit queer.

NL Sinds de eeuwwisseling zijn LHBT personages in televisie series niet langer afwezig of gerepresenteerd als eendimensionaal, betreurenswaardig of stereotiep. Toch zijn vele van deze representaties gevormd om te passen binnen het dominante, normatief discours rond gender en seksualiteit in de Westerse beschaving. In deze lezing zal ik de verschillende wijzen van voorstelling bespreken en argumenteren waarom bepaalde representaties stereotiep en aanstootgevend zijn en andere transgressief en zonderling.

EN Since the turn of the twenty-first century LGBT characters are no longer absent or represented as one-dimensional, deplorable or stereotypical in television series. Yet, many of these representations are shaped to fit the dominant and normative discourses on gender and sexuality in Western societies. In this lecture, I will demonstrate the diverse ways used to depict LGBTs and argue why some representations can be considered stereotypical and offensive and others transgressive and queer.

15:00 > 16:00 Bridget Conor (UK) ‘It’s getting better’: Debating and researching inequalities in television production studies

FR Lors de cette discussion, Bridget Conor abordera quelques-uns des débats actuels dans la recherche académique, l’élaboration des politiques et la couverture médiatique, à propos des inégalités dans l’industrie culturelle. Elle se penchera en particulier sur la façon dont ces débats transparaissent dans les productions télévisées, en s’appuyant sur ses propres recherches en matière d’écriture scénaristique, de genre et de travail de création.

NL In dit gesprek zal Bridget Conor het hebben over de huidige debatten in het academisch onderzoek naar, de beleidsvorming rond en de mediabelangstelling voor ongelijkheden in de culturele industrieën. Ze zal vooral nader ingaan op de manier waarop deze debatten in televisieproducties worden gevoerd, steunend op haar eigen onderzoek naar scenarioschrijven, gender en creatief werk.

EN In this talk, Bridget will discuss some of the current debates in academic research, policymaking and media coverage which focus on the problem of inequalities in the cultural industries. She will particularly focus on how these debates play out in television production, drawing on her own research on screenwriting, gender and creative labour.

16:30 > 17:30 Keynote Nicola Lusuardi Make it Original. Aesthetical research and innovation in new serial storytelling

FR Depuis 1990, Nicola Lusuardi travaille comme auteur dramatique pour différentes sociétés de production ainsi que comme scénariste, script doctor et superiveur pour les chaines de télévision RAI, Mediaset, Sky. Il est également consultant et tuteur au TorinoFilmLab-Interchange et au Biennale College

NL Nicola Lusuardi werkt sinds 1990 as voor verschillende productiehuizen als story editor en voor televisie netwerken als RAI, Mediaset, Sky. Hij werkt ook als consultant en leraar in TorinoFilmLab-Interchange en Biennale College.

EN Since 1990, Nicola Lusuardi has been working as a playwright for several production companies and as a screenwriter, story editor and supervisor for television networks RAI, Mediaset, Sky. He also works as a script consultant and tutor in TorinoFilmLab-Interchange and Biennale College.

17:30 > 19:00 Round table Researching Arena Through Characters

With Chris Brancato (Narcos, USA), Nicolas Peufaillit (Les revenants, FR), Helen Perquy (Quiz me Quick, BE) and Nicola Lusuardi (1992, IT), Bridget Conor (UK)

without any concession to the naïve and sentimental utopias that continue to litter our perception of the harsh reality. Aldama’s prose is in your face and Long Stories Cut Short is amongst the most depressing books one can imagine. A welcome reply to all romantic views on the land of milk and honey (“She might be able to go home, the doctor announces. /He can only think: Hurry up and die.”, p. 171).

without any concession to the naïve and sentimental utopias that continue to litter our perception of the harsh reality. Aldama’s prose is in your face and Long Stories Cut Short is amongst the most depressing books one can imagine. A welcome reply to all romantic views on the land of milk and honey (“She might be able to go home, the doctor announces. /He can only think: Hurry up and die.”, p. 171).

developed in collaboration with

developed in collaboration with

They are instead screenplays, but screenplays that explicitly present themselves as unfilmable –less in the sense of parodies of screenwriting (this is what Boris Vian will do twenty years later in his fake scenario for the adaptation of I Will Spit on Your Graves) than as attempts to materialize the abstract idea of the ruin of all things solid in an era whose muse was destruction.

They are instead screenplays, but screenplays that explicitly present themselves as unfilmable –less in the sense of parodies of screenwriting (this is what Boris Vian will do twenty years later in his fake scenario for the adaptation of I Will Spit on Your Graves) than as attempts to materialize the abstract idea of the ruin of all things solid in an era whose muse was destruction.

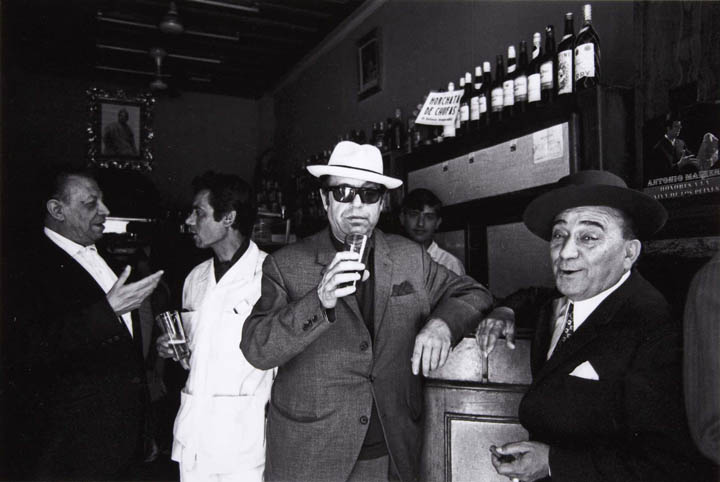

If you travel to Granada this Spring, don’t go to one of the flamenco shows that litters the touristic areas of the city. Forget about them, and go immediately to the Alhambra; more precisely, the photography exhibition curated by Concha Gόmez (professor at the Carlos III University in Madrid). This exhibition offers an amazing retrospective of the work of Colita – artist name of Isabel Steva (°1940) – one of the first professional female press photographers in Spain who has always been fascinated by the world of the gypsies and flamenco. Speculations on the misrepresentation of real and authentic culture immediately vanish when entering the exhibition, which is a model of great photography as well as curatorial intelligence. What makes the experience so strong is the complete coincidence of the various levels of mediation. One witnesses for example the intimate knowledge of the culture the artist wants to represent (the photographer is not an outsider of the flamenco culture). Furthermore, the curator has built a strong personal relationship with the photographer, as shown by a wonderful filmed interview in the exhibition which refrains from overloading the images with all kinds of didactic captions. There is a strong awareness of the historical and political complexities of flamenco, a longtime marginalized art, created by marginalized people. One cannot therefore simply document flamenco from the outside or by detaching it from the rest of a living culture where current ideas on art prevent us from seeing and feeling what is really happening. An additional level of mediation is the perfect capacity of disclosing the “duende”, the epiphany (?), with an economy of means that is shared by the flamenco artist, the photographer and the curator, and finally, the desire to not only focus on the exceptional value of masterpieces (although neither Colita nor Gόmez tend to hide the empowering presence of exceptional figures).

If you travel to Granada this Spring, don’t go to one of the flamenco shows that litters the touristic areas of the city. Forget about them, and go immediately to the Alhambra; more precisely, the photography exhibition curated by Concha Gόmez (professor at the Carlos III University in Madrid). This exhibition offers an amazing retrospective of the work of Colita – artist name of Isabel Steva (°1940) – one of the first professional female press photographers in Spain who has always been fascinated by the world of the gypsies and flamenco. Speculations on the misrepresentation of real and authentic culture immediately vanish when entering the exhibition, which is a model of great photography as well as curatorial intelligence. What makes the experience so strong is the complete coincidence of the various levels of mediation. One witnesses for example the intimate knowledge of the culture the artist wants to represent (the photographer is not an outsider of the flamenco culture). Furthermore, the curator has built a strong personal relationship with the photographer, as shown by a wonderful filmed interview in the exhibition which refrains from overloading the images with all kinds of didactic captions. There is a strong awareness of the historical and political complexities of flamenco, a longtime marginalized art, created by marginalized people. One cannot therefore simply document flamenco from the outside or by detaching it from the rest of a living culture where current ideas on art prevent us from seeing and feeling what is really happening. An additional level of mediation is the perfect capacity of disclosing the “duende”, the epiphany (?), with an economy of means that is shared by the flamenco artist, the photographer and the curator, and finally, the desire to not only focus on the exceptional value of masterpieces (although neither Colita nor Gόmez tend to hide the empowering presence of exceptional figures). On 8 and 9 December, the UCL based research group GIRCAM (a French acronym that refers to the study of cultures “on the move”) organizes a conference on this key issue. The venue is Mons (and as all readers of this blog already know, any opportunity is good to visit this wonderful city), and the diversity of the program is exciting.

On 8 and 9 December, the UCL based research group GIRCAM (a French acronym that refers to the study of cultures “on the move”) organizes a conference on this key issue. The venue is Mons (and as all readers of this blog already know, any opportunity is good to visit this wonderful city), and the diversity of the program is exciting.

All this to say that I was cruelly disappointed by two recent “new” works, which both claim a certain form of novelty, if not avant-garde aura, but which rapidly collapse in light of the longer history of their art: first “Roman”, a parodic collage (mindlessly labeled “graphic poem” by the journal that devotes a special issue to the newest kid on the graphic novel block) by Luc Fierens (a Flemish artist enthusiastically embraced by the in-crowd as a representative of the post-neo-avant-garde); second Carpet Sweeper Tales, an equally parodic photo-cum-captions collage by Julie Doucet (best known for the feminist punk comics she published in the 1990s).

All this to say that I was cruelly disappointed by two recent “new” works, which both claim a certain form of novelty, if not avant-garde aura, but which rapidly collapse in light of the longer history of their art: first “Roman”, a parodic collage (mindlessly labeled “graphic poem” by the journal that devotes a special issue to the newest kid on the graphic novel block) by Luc Fierens (a Flemish artist enthusiastically embraced by the in-crowd as a representative of the post-neo-avant-garde); second Carpet Sweeper Tales, an equally parodic photo-cum-captions collage by Julie Doucet (best known for the feminist punk comics she published in the 1990s). and much harder and harsher forms– of parody in the pale and dull remakes by Fierens and Doucet that prove disappointing. No mention here of the Situationnist détournements, those for instance by Marcel Mariën who already in the 60s critically appropriated the aesthetics and ideology of the photonovel. No mention either of Barbara Kruger’s later attacks on consumer society through the combination of photographs and overlaid stereotypical statements. And one could go back to Surrealist Max Ernst (whose collage picture novels are now being reissued) or the political art of John Heartfield –the list is almost endless (in the comics field, why not remember Art Spiegelman’s early collages or the many constrained works produced by the Oubapo group and their many sympathizers).

and much harder and harsher forms– of parody in the pale and dull remakes by Fierens and Doucet that prove disappointing. No mention here of the Situationnist détournements, those for instance by Marcel Mariën who already in the 60s critically appropriated the aesthetics and ideology of the photonovel. No mention either of Barbara Kruger’s later attacks on consumer society through the combination of photographs and overlaid stereotypical statements. And one could go back to Surrealist Max Ernst (whose collage picture novels are now being reissued) or the political art of John Heartfield –the list is almost endless (in the comics field, why not remember Art Spiegelman’s early collages or the many constrained works produced by the Oubapo group and their many sympathizers).

Schlanger’s newest book, Trop dire ou trop peu. Essai sur la densité littéraire (Paris, Hermann, 2016) addresses a question that no one who takes writing seriously can ever avoid: Where do I stop? How can I be sure that I have said enough (for to say more would be a bore to the reader)? And how do I know that I have to say something more (for if I don’t my reader will discard my text as opaque or incomprehensible). Very simple questions, but real questions, which can never be fully answered.

Schlanger’s newest book, Trop dire ou trop peu. Essai sur la densité littéraire (Paris, Hermann, 2016) addresses a question that no one who takes writing seriously can ever avoid: Where do I stop? How can I be sure that I have said enough (for to say more would be a bore to the reader)? And how do I know that I have to say something more (for if I don’t my reader will discard my text as opaque or incomprehensible). Very simple questions, but real questions, which can never be fully answered.