By Fred Truyen

In May, we launched the Europeana Thematic channel on Photography – “Europeana Photography”. Cultural Studies Leuven was responsible for the curation – being a member of Photoconsortium, the expert hub on photography for Europeana. The channel opens up the richness of photographic heritage in Europeana by telling stories from a point of view that combines a sense for history with a deep understanding of the materiality and the photographic techniques, and how these interact with the way photographers used the medium to produce their magic. Photography is and will always be this raw, “in your face” medium, that directly imprints in the brain a compelling, unescapable “image”. Even though photographs have lied and deceived in so many ways, it is hard to resist their immediacy and supposed “realism”. Photographs have actually shaped our views on “facts”, events, news items and perceptions of conflicts throughout history since their invention in 1839. In Europeana Photography, curator Sofie Taes brings you an insight in the development of this medium and art through the centuries, by telling stories in the form of virtual exhibitions, such as “The Pleasure of Plenty” – in fact a series devised in different seasons as you might expect in the Netflix age -, galleries and so-called “browse entry points” or predefined queries, like the one on “cartes de visite”. Of course, if you are not afraid to browse through thousands and thousands – we can safely say more than 2.3 million images – just use the search box!

But for this blog post, let’s discuss some old photo techniques and how they define the character of the photograph. Let’s go from the oldest to newer ones. It is still very difficult to do justice to a Daguerreotype, as it is the result of a process that gives amazingly sharp images, with a typical silver brilliance. As it required a sealed glass encasing, Daguerreotypes in their frame are nice, precious objects. However, there is almost no shadow to be seen – Daguerreotypes are only sensitive to ultraviolet light. It has a rather dull, even tonality. This gives the images a kind of clinical, lifeless feeling. The object has a charming “metal” gloss, mostly improved through a gilding process. Often they were coloured in, as the example shown. A Daguerreotype (named after its inventor Louis Daguerre) is normally a mirrored image, although it was possible to reverse this by using prisms. It is very shiny and appears only when viewed from a certain angle.

What a contrast with the process developed by Louis Daguerre’s rival John Talbot, the calotype, which is a two-phased process with a calotype paper negative used to make salt print positives, by direct contact, exposed in the sun. The Daguerreotype produces a unique object, by contrast the calotype/salt print process allows for multiple copies to be made. What a warmth the sun gives to this all, and the paper negatives bring high contrasts and shadows, but also some blurriness and a soft feel. While the Daguerreotype quickly became the photography of science, the calotype won over the hearts and minds of the general public, offering dreamy impressions rather than naked facts.

My favourite photographic process is without any doubt the wet collodion process, commonly called wet plate photography. Collodion is a brownish, viscous fluid, to be poured on a hard support – can be a glass or metal plate – that contains silver halides which can be sensitized when put in a bath of silver nitrate. That’s why it is “wet” when you take the photo – the whole process taking on average about 15 minutes for one shot. This procedure superseded the older techniques from about 1854 onwards. While it combines the sharpness of the Daguerreotype with a certain ease of use, it is the absolute king of contrast, producing a deep silver black and a richness in shadows.

Combine this with the properties of the big cameras used to make these photos – glass or metal plates sized 5×5 up to 14×14 inch and higher – and the big lens with an abhorrent large opening and the resulting very narrow depth of field, you get extremely forceful portraits, as Julia Margaret Cameron showed with such prowess, thereby defining portrait photography as an art in its own right! While the contrast is high, the dynamic range is rather limited, about half of that of digital photography, which in its turn is also not really a champion. A wet collodion photo is brutal: it reveals every detail in a face, due to its sensitivity for ultraviolet light, of which the short waves can perfectly map the slightest irregularities on the skin. A wet collodion photo on glass is called an ambrotype, when it is on a metal sheet it is often called a ferrotype or a tintype. The reproduction below however is a paper print.

Wet plate photography is increasingly popular with current portrait and landscape photographers as it is a relatively safe procedure and adds an astonishing level of detail and quality that are difficult to match by digital cameras. This is not only the case for professional photography, but also for artistic photography where photographers such as Sally Mann have made decisive contributions to revive the genre.

The subsequent silver gelatine process would become the standard monochrome process in the later nineteenth and twentieth century, until the advent of course of digital photography. This easy to use, safe and scalable process would establish analogue photography. It is super clean and has all the good properties, but to me – and to many vintage enthusiasts rediscovering early photography – it cannot compete with the raw force of the wet collodion based ambrotypes or tintypes, let alone with the poetry of the salt prints. But then again its ease of use – dry plates or celluloid film – and higher sensitivity – resulting in shorter exposure times – boosted the creative development of photography, opening it up to sports, action, movement, depth of field etc., where older photographic techniques were essentially constrained to rather static portraits and landscapes.

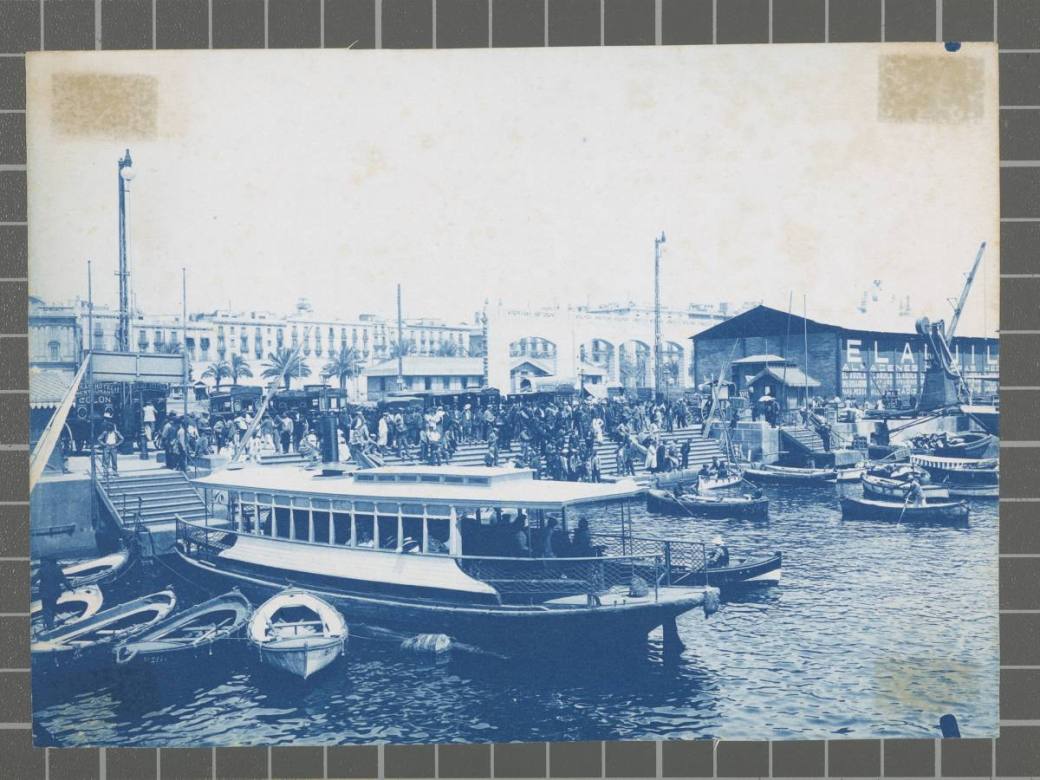

A cyanotype is a specific process producing, as the word says, a “blue” image. There is a nice gallery of those on the channel. As this was an easy process, it was often used to quickly make prints to verify photos before making the actual commercial print. It was also used for the so-called “blue-prints” of designs and drawings. In fact the process was discovered by Sir John Herschell, one of the founding fathers of photography.

A last technique to mention is an early colour technique, developed by the brothers Lumière. It is the autochrome. In fact, this is a kind of diapositive. Onto the glass plate a layer of coloured starch grains – red, green, blue – is attached, which filters the incoming light. This layer stays with the photograph, which is then shown by backlighting. You get a kind of pointillist effect, and the colours produced have a special warmth that you usually do not find in current, more blueish and colder colour techniques.

Is the growing popularity of vintage photography yet another pointless surge of nostalgia in a world of digital banality and immediacy? A kind of allergic reaction to the emptiness of the selfie? Or is the photograph indeed something else than just the light information captured, but a magic that occurs in the chemistry of the material object that is the vintage print or plate ? This is for you to decide, but hopefully only after spending some hours on Europeana Photography!

Hazan’s crossing of Paris leads him from the south (Ivry) to the north (Saint-Denis) and focuses on the “center” of Paris; that is, the twenty neighborhoods that can be found “inside” the beltway, which both prevents the traditional city to grow and protects it from the dangers of the less wealthy suburban circles that surround it (some French view Saint-Denis the way some Belgians view Molenbeek). Yet the margins are permanently present: geographically, humanly, culturally, politically speaking. The major aim of Hazan’s book is to disclose the “popular” aspects of the capital, which resist the galloping gentrification, and to highlight the continuity of a revolutionary tradition in the city.

Hazan’s crossing of Paris leads him from the south (Ivry) to the north (Saint-Denis) and focuses on the “center” of Paris; that is, the twenty neighborhoods that can be found “inside” the beltway, which both prevents the traditional city to grow and protects it from the dangers of the less wealthy suburban circles that surround it (some French view Saint-Denis the way some Belgians view Molenbeek). Yet the margins are permanently present: geographically, humanly, culturally, politically speaking. The major aim of Hazan’s book is to disclose the “popular” aspects of the capital, which resist the galloping gentrification, and to highlight the continuity of a revolutionary tradition in the city.

Jean-Christophe Menu is one of the major voices of alternative comics in France, both as an author and as the co-founder of L’Association, the leading publisher of French comix in the period of his 20 years editorship (he resigned a couple of years ago). He is above all a living paradox: the angry young man of the French bande dessinée scene, he is also the holder of a PhD on the subject (moreover an excellent one, frequently used and quoted in academic research: La Bande dessinée et son double, 2011); the living example of authentic visual thinking, he is also an author who does not make any real distinction between his drawings and his writings. His new book is the perfect yet open synthesis of all these forces and tendencies.

Jean-Christophe Menu is one of the major voices of alternative comics in France, both as an author and as the co-founder of L’Association, the leading publisher of French comix in the period of his 20 years editorship (he resigned a couple of years ago). He is above all a living paradox: the angry young man of the French bande dessinée scene, he is also the holder of a PhD on the subject (moreover an excellent one, frequently used and quoted in academic research: La Bande dessinée et son double, 2011); the living example of authentic visual thinking, he is also an author who does not make any real distinction between his drawings and his writings. His new book is the perfect yet open synthesis of all these forces and tendencies. without any concession to the naïve and sentimental utopias that continue to litter our perception of the harsh reality. Aldama’s prose is in your face and Long Stories Cut Short is amongst the most depressing books one can imagine. A welcome reply to all romantic views on the land of milk and honey (“She might be able to go home, the doctor announces. /He can only think: Hurry up and die.”, p. 171).

without any concession to the naïve and sentimental utopias that continue to litter our perception of the harsh reality. Aldama’s prose is in your face and Long Stories Cut Short is amongst the most depressing books one can imagine. A welcome reply to all romantic views on the land of milk and honey (“She might be able to go home, the doctor announces. /He can only think: Hurry up and die.”, p. 171). Erin Manning and Brian Massumi will discuss their development of ‘The 3 Ecologies Institute’ at SenseLab (

Erin Manning and Brian Massumi will discuss their development of ‘The 3 Ecologies Institute’ at SenseLab (