By Jan Baetens

Laurent de Sutter

Jack Sparrow. Manifeste pour une linguistique pirate

Bruxelles, Les Impressions Nouvelles, 2018, 1128 p., 12 euros

ISBN : 9782874496479

If popular culture is culture for the millions, entertaining and easy to understand, many great readers and critics are well aware of the fact that this fundamental openness is not to be confused with shallowness or lack of sophistication. Popular culture has a lot to tell –not always of course, but this also applies to high culture, many forms of which are equally dead matter. The truth of drawing is told by Hergé as well as Rembrandt. If you want to understand the unconscious, a Hitchcock movie proves no less useful than Un chien andalou. And for the mysteries of the heart, it is not forbidden to prefer a romance comic to Jane Austen.

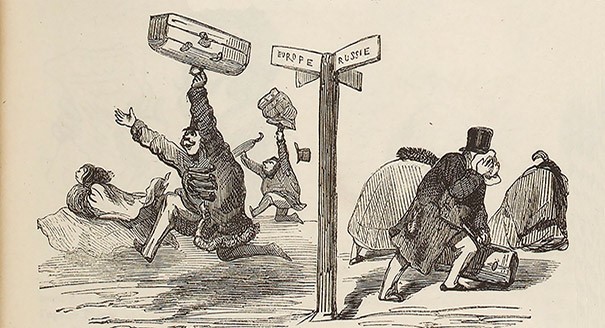

The Pirates of the Caribbean may not be compulsory viewing in serious film classes (and to make things even worse: this is a Disney franchise, based on a Disney theme park attraction, catering to Disney fans, etc.) but this brilliant and crispy essay by Laurent de Sutter shows that it is time to put all prejudices aside.

A specialist of law theory and prolific author and lecturer (will he be called one day the Belgian Zizek?), Laurent de Sutter explores in Jack Sparrow the theme of piracy from a linguistic point of view. For to be a pirate is not only to make the choice of a way of life that rejects the ruling order, based on fixed rules imposed by a ruling class. Such a pirate choice is only possible thanks to a special use of language, which de Sutter calls the pirate use, based on the radical combination of the fireworks of verbal performance and the denial of language’s referential function. In Jack Sparrow, de Sutter analyzes this piracy in a permanent braiding of the Johnny Depp character and a wide range of cultural theories on the role and nature of language in society.

It should not come as a surprise that Baudrillard’s ideas on seduction and Lacan’s rethinking of the relationship between truth and desire occupy a key place in his argumentation. These high-cultural references, however, do not hinder the joyful anarchy Laurent de Sutter is defending. His book is a roller-coaster of intellectual provocations and exhilarating formulas, of language transformed into a sound and image spectacle as well as high philosophy mixed with fun and laughter. Serious readers will not be changed into pirates after having read this book, but Jack Sparrow is definitely a work they are in need of.

Although there exist quite some studies on the journal, the study by Wendy Michallat is the very first one to rethink its history in a broader perspective, not just that of comics culture, but that of culture at large. And the result is absolutely breath-taking. First of all because Michallat gives a very detailed yet nuanced and well written overview of the various periods of the magazine, whose history is one of nearly permanent crisis and eternal attempts to relaunch new formats and formulas in a publication niche that was much less profitable than it was often thought. Second, and most importantly, because the author succeeds in doing what other studies fail to do, namely explaining the systematic changes in the magazine’s policy.

Although there exist quite some studies on the journal, the study by Wendy Michallat is the very first one to rethink its history in a broader perspective, not just that of comics culture, but that of culture at large. And the result is absolutely breath-taking. First of all because Michallat gives a very detailed yet nuanced and well written overview of the various periods of the magazine, whose history is one of nearly permanent crisis and eternal attempts to relaunch new formats and formulas in a publication niche that was much less profitable than it was often thought. Second, and most importantly, because the author succeeds in doing what other studies fail to do, namely explaining the systematic changes in the magazine’s policy.