By Sofie Taes

Girl with greased quiff and leather jacket, 1959

AB Helsingborgs-Bild

Kulturmagasinet, Helsingborgs museer. Public Domain

A promising premise

Much like scents, flavours and music, photographs are powerful triggers of memory. So what better medium to recall a past as recent and as iconic as early postwar Europe…? For about a year, the consortium involved in the project ‘50s in Europe Kaleidoscope’ has been diving into collections of libraries, archives and commercial agencies across Europe, to trace the tracks of the fifties in photography.

Much like scents, flavours and music, photographs are powerful triggers of memory. So what better medium to recall a past as recent and as iconic as early postwar Europe…? For about a year, the consortium involved in the project ‘50s in Europe Kaleidoscope’ has been diving into collections of libraries, archives and commercial agencies across Europe, to trace the tracks of the fifties in photography.

‘50s in Europe Kaleidoscope’, a project co-financed by the European Union in the framework of the Connecting Europe Facility Programme, aims at leveraging photographic collections depicting the 1950s in Europeana: Europe’s most trusted and extensive portal to cultural heritage. To increase engagement with Europeana, Kaleidoscope focuses on crowdsourcing and co-curation, inviting European citizens to share personal stories and explore common history.

Compound eye

In the process of exploring and analyzing relevant photo collections for the project, the expected imagery of the era as a time of intrinsic happiness surfaced quite quickly. The rosy outlook on the fifties as a modern-age, bright-coloured paradise, in which horrors from the past seemed to be gone forever, is frozen in our collective memory and fed by nostalgia of the baby boomers. Yet in recent years, a more holistic view has taken root: a layered, nuanced narrative that we soon started to identify in the picture collections at hand.

Statue of Stalin taken down in Budapest, October 1956

National Széchényi Library. CC BY-NC-SA

With project partners from both sides of the Cold War divide, our perspective quickly turned ‘bifocal’. The fifties were indeed the breeding ground for Europe as we know it today, but at the time political regimes, economic circumstances, societal developments, levels of prosperity and consumer trends were very different in the east and west, north and south. From a political point of view, Europe was a shattered landscape, trying to cope both with internal tensions (dictatorial regimes in Spain and Portugal, Civil War in Greece, revolution in Hungary, …) and the all-dominating dynamics between east (/USSR/communism) and west(/US/capitalism). Colonial empires were dissolving, only reinforcing the vast waves of migration that drove hundreds or thousands of citizens out of – and others into – the continent. Peace brought prosperity – after the first frugal years following WWII – but not in equal measure throughout Europe.

![[Automòbil triauto]](https://culturalstudiesleuven.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/road_693216.jpg?w=1040)

The Messerschmitt Kabinenroller in the streets of Girona, July 1954

Martí Massafont Costals

Ajuntament de Girona / CRDI. CC BY-NC-ND

Showtime: exhibition on the go

Catalogue in Print, August 2019

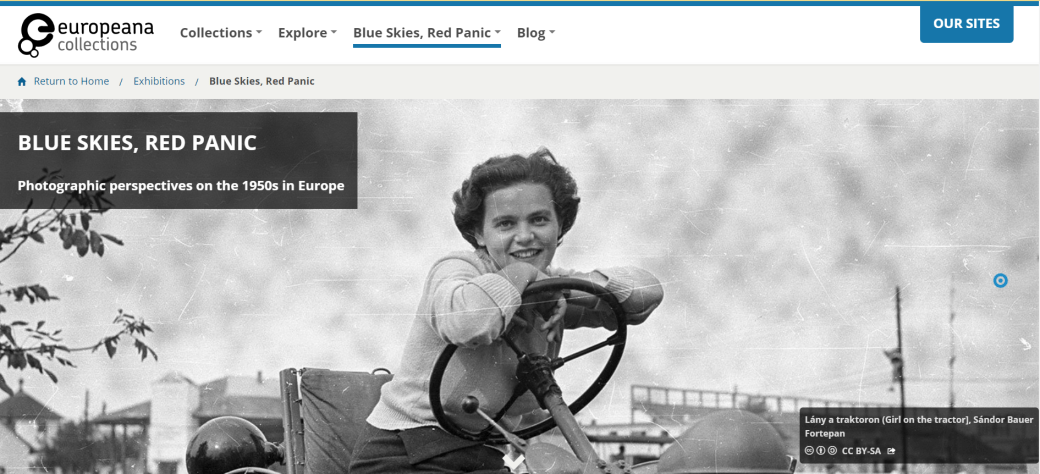

This historical backdrop, as attested to by the collections of our project partners, was the point of departure for a stroll through a decade that is in need of a refreshed historical approach. In the framework of the project, an important showcase to convey this perspective is the physical exhibition created and curated by KU Leuven’s CS Digital: Blue Skies, Red Panic.

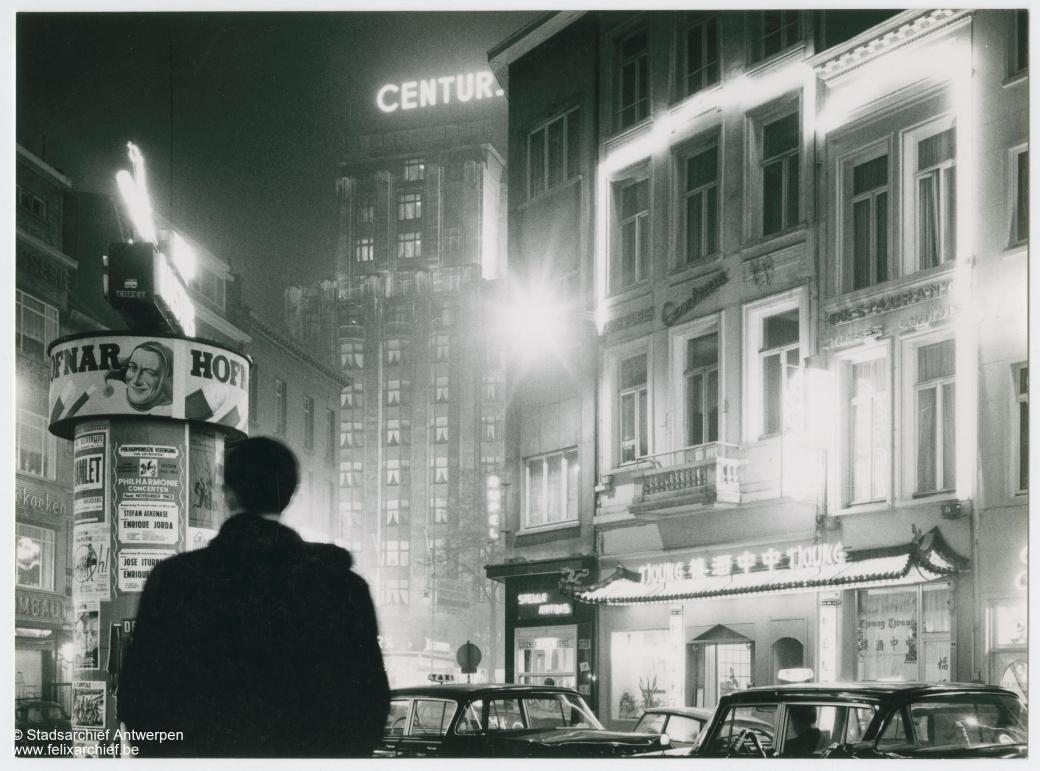

With powers as opposite as the capitalist and communist bastions, and phenomena as contrasting as consumerism and crisis, emancipation and dictatorship, traditionalism and counterculture, this exhibition could have easily turned into a simple game of contrasts and opposites. Yet while the pictures we selected are very much black and white, the stories they convey boast an endless range of greys. Through these shades, the reflection of the 1950s gains nuance, color and depth.

On 6 September, in the splendid palazzo Lanfranchi (Museo della grafica) situated alongside the ‘lungarni’ by the river Arno, Blue Skies, Red Panic was baptized. The setup of 26 vintage images, digitized and printed on large-size panels, deployed a rich narrative in 11 chapters boasting duos and trios of images to shed light on huge trends, interesting undercurrents, big history and personal stories. After its first instance in Pisa, the exhibition recently traveled to Girona where it will re-open at the Centre Cultural la Mercè on November 12th. In January we’ll be showing Blue Skies at the KU Leuven Campus Carolus premises in the heart of historical Antwerp, after which it will go on to visit Kulturforum Berlin (February 2020).

Blue Skies, Red Panic in Pisa, vernissage of September 6th

In the mean time, a completely reworked and extended version of the exhibition has been tailor made for Europeana.eu. Launched only last week, Blue Skies will be open to a large online community.

Blue Skies, Red Panic on europeana.eu: similar scenario, remodeled showcase

Finally, an interactive virtual version will be created with the MuPop-app developed by Amsterdam-based company Noterik, allowing visitors to control the narration and listen to the stories simply by using their smartphone. Blue Skies MuPop will be debuting at the Day of Science at KU Leuven (24 November), will go on to be shown at Coventry University (3 December) and is bound to visit more partner premises in months to come.

Musings

Campaign image of the Swedish department store Nordiska Kompaniet, 1953

Erik Holmén

Stiftelsen Nordiska museet. CC BY-NC-ND

Having had the pleasure to curate this exhibition from the ground up, I am excited by the way it lends itself to being transformed for different platforms, using different media, offering different modes of interaction and participation. The fact that a beautiful, printed catalogue will serve as the everlasting reminder of a splendid project and the unique creative opportunities it has offered me, is a genuine joy as well. But by far the most rewarding result of this effort are the reactions received so far from people who visited the Pisa-installment, read the catalogue or explored the exhibition via Europeana.

There’s awe for the outstanding quality of the images, smiles of recognition, gasps of surprise, reflection, introspection and discussion. Someone wrote to me: ‘What I liked the most is how each image tells a story, yet the text demonstrates there’s more than what meets the eye’. With the open yet critical attitude that is at the core of CS Digital as a constant driver as well as a goal, such feedback is the best return on (creative) investment I could have wished for.

Feeling curious or creative?

We warmly invite you to explore the photographs and stories via photoconsortium.net, where all images and texts can be accessed directly and the exhibition catalogue can be downloaded for free. Via the same website, it’s possible to enter the educational portal and retrieve reusable material. Visit fifties.withculture.eu to create your own fifties collections with images from repositories such as Europeana or your own photographic memories. Finally, we’d be delighted if you could help us help more people retrieve these gems by participating in our annotation campaign on withcrowd.eu.

We warmly invite you to explore the photographs and stories via photoconsortium.net, where all images and texts can be accessed directly and the exhibition catalogue can be downloaded for free. Via the same website, it’s possible to enter the educational portal and retrieve reusable material. Visit fifties.withculture.eu to create your own fifties collections with images from repositories such as Europeana or your own photographic memories. Finally, we’d be delighted if you could help us help more people retrieve these gems by participating in our annotation campaign on withcrowd.eu.

Annotation sprint

Annotation sprint The Bibliotheca Wittockiana is the museum of book arts and bookbinding in Brussels. Besides maintaining a prestigious collection of both historical and contemporary books (and having a weirdly large number of baby rattles), they also host a few temporary exhibitions each year. From September 19th until January 20th, the artist Olivier Deprez (Binche, 1966) presented his project WREK in the exhibition WREK NOT WORK, curated by Géraldine David and Jan Baetens.

The Bibliotheca Wittockiana is the museum of book arts and bookbinding in Brussels. Besides maintaining a prestigious collection of both historical and contemporary books (and having a weirdly large number of baby rattles), they also host a few temporary exhibitions each year. From September 19th until January 20th, the artist Olivier Deprez (Binche, 1966) presented his project WREK in the exhibition WREK NOT WORK, curated by Géraldine David and Jan Baetens.

Since the scholarly production on Neorealism continues to be superabundant (and this in more than one language), the new book by Francesco Pitassio may not immediately be distinguished by all those interested in the field, but one can be sure that the outstanding qualities of this book will soon turn it into a real classic, both in the specific domain of Neorealist cinema and in the broader domain of film and cultural studies in general. Pitassio’s study is indeed much more than a new take on Neorealism; it is also a landmark reflection on the theoretical and methodological questions that define film history. In this regard, its stakes and insights are of interest to all those working on film as cultural form, just as, for instance, the book by Antoine de Baecque on cinephilia as a form of film culture, which partially covers similar ground (cf. La cinéphilie. Invention d’un regard, histoire d’une culture, 1944-1968, Fayard, 2013).

Since the scholarly production on Neorealism continues to be superabundant (and this in more than one language), the new book by Francesco Pitassio may not immediately be distinguished by all those interested in the field, but one can be sure that the outstanding qualities of this book will soon turn it into a real classic, both in the specific domain of Neorealist cinema and in the broader domain of film and cultural studies in general. Pitassio’s study is indeed much more than a new take on Neorealism; it is also a landmark reflection on the theoretical and methodological questions that define film history. In this regard, its stakes and insights are of interest to all those working on film as cultural form, just as, for instance, the book by Antoine de Baecque on cinephilia as a form of film culture, which partially covers similar ground (cf. La cinéphilie. Invention d’un regard, histoire d’une culture, 1944-1968, Fayard, 2013).

On January 9th the doors of KU Leuven Campus Antwerpen will open for the Vernissage of not only “Blue Skies, Red Panic”, but also “Generation A”. From 6pm onwards visitors are welcome to stroll through the exhibition engaging with heritage and building bridges to today’s life, experiencing the present art-scene of upcoming artists in Antwerp. The Vernissage is accompanied by a reception and opening speeches by Prof. Dr. Bart Van Looy, Academic Dean of Flanders Business School, and Professor Fred Truyen, from the Cultural Studies Department of KU Leuven.

On January 9th the doors of KU Leuven Campus Antwerpen will open for the Vernissage of not only “Blue Skies, Red Panic”, but also “Generation A”. From 6pm onwards visitors are welcome to stroll through the exhibition engaging with heritage and building bridges to today’s life, experiencing the present art-scene of upcoming artists in Antwerp. The Vernissage is accompanied by a reception and opening speeches by Prof. Dr. Bart Van Looy, Academic Dean of Flanders Business School, and Professor Fred Truyen, from the Cultural Studies Department of KU Leuven. sébastien conard

sébastien conard

Brian Glavey, “Having a coke with You is Even More Fun Than Ideology Critique”, PMLA, Oct. 2019, pp. 996-1011

Brian Glavey, “Having a coke with You is Even More Fun Than Ideology Critique”, PMLA, Oct. 2019, pp. 996-1011

Much like scents, flavours and music, photographs are powerful triggers of memory. So what better medium to recall a past as recent and as iconic as early postwar Europe…? For about a year, the consortium involved in the project ‘50s in Europe Kaleidoscope’ has been diving into collections of libraries, archives and commercial agencies across Europe, to trace the tracks of the fifties in photography.

Much like scents, flavours and music, photographs are powerful triggers of memory. So what better medium to recall a past as recent and as iconic as early postwar Europe…? For about a year, the consortium involved in the project ‘50s in Europe Kaleidoscope’ has been diving into collections of libraries, archives and commercial agencies across Europe, to trace the tracks of the fifties in photography.

![[Automòbil triauto]](https://culturalstudiesleuven.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/road_693216.jpg?w=1040)

We warmly invite you to explore the photographs and stories via

We warmly invite you to explore the photographs and stories via